I read an article in the local beek newsletter about someone who had a hive on a scale. It turns out that an oceanographer (Wayne Esaias) who works for NASA is also a beekeeper, and he has brought together a group of volunteer beekeepers around the country who send him data on the weights of their hives. For more info about this project, check out the HoneyBeeNet Web site (http://honeybeenet.gsfc.nasa.gov/). Below are some photos of my scale hive and the initial data plots.

I moved one of the hives a few feet in front of its customary position to prepare the site for the scale. This turned out to be fairly straightforward.

Hive moved in front of the future scale position; it stayed on the cart for a week, and the bees didn't seem to mind.

Dr. Hurst found someone with a couple of farm scales for sale. Mine is a Fairbanks 1124A, a classic, but it was in rough shape. I took it apart, scraped off the rust, beat out the dents with a rubber hammer, and repainted it.

The scale hive protocol on HoneyBeeNet told how to calibrate the scale; it turned out this scale was quite accurate and very precise. I made a cover out of campaign signs and aluminum flashing to cover the balance arm, registered the site with NASA, and started sending in data.

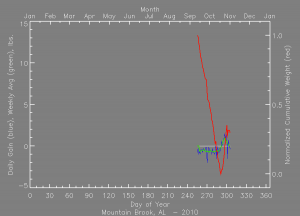

Here is a plot of my scale hive data from early September through November. The red line is the “normalized cumulative weight”, which accounts for equipment changes and feeding. As shown below, this hive was blowing through its food supply, and I had to feed it almost continuously for the first few weeks. The spike upward is due to a modest nectar flow in October that I would have never noticed if I hadn’t been weighing the hive daily.

Dr. Esaias is interested in correlating scale hive data with satellite vegetation photos to get a handle on global warming, colony collapse disorder, and even the spread of Africanized honey bees, but this project has given me an appreciation for assessing honey bee colony health by weighing the hives. With my scale hive as a reference, I can confidently heft all the other scales in the yard to get an idea which hives might need some extra attention.